Indonesia – the only Southeast Asian country to propose new coal plants in 2024 – has been steadily introducing biomass into its power mix in the past few years as part of its renewable energy push.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

But a new study has warned that the state power utility PLN’s promotion of biomass co-firing – using wood and agricultural waste as feedstock – mitigates negligible emissions and potentially risks releasing more pollutants, due to lax standards.

Calling the practice a “false strategy”, environmental non-profit Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA)’s latest analysis found that burning, or “co-firing”, organic materials in power plants is only expected to reduce around 1.5 to 2.4 per cent of the country’s aggregated coal power emissions.

The government’s current target to replace 10 per cent of coal in 52 existing PLN-owned power plants by 2050 is projected to merely deliver 9 per cent, 7 per cent and 10 per cent reductions in health-harming air pollutants like particulate matter (PM), nitrogen oxides (NOx) and sulphur dioxide (SO2), respectively, estimated CREA.

Its projection model assumes adherence to emissions standards set for coal plants, which do not cover air pollutants like carbon monoxide, and heavy metals like lead, which are linked to combusting specific feedstock in biomass power plants.

“While the regulation defines limits for thermal power plants that operate using a blend of coal, oil and natural gas, there are no specific air pollution limits set for coal-fired power plants where biomass co-firing is implemented,” stated CREA in its report. Therefore, if PLN’s coal fleet only adheres to the emissions standards for coal power plants, other health-harming pollutants could end up being released without any monitoring, it added.

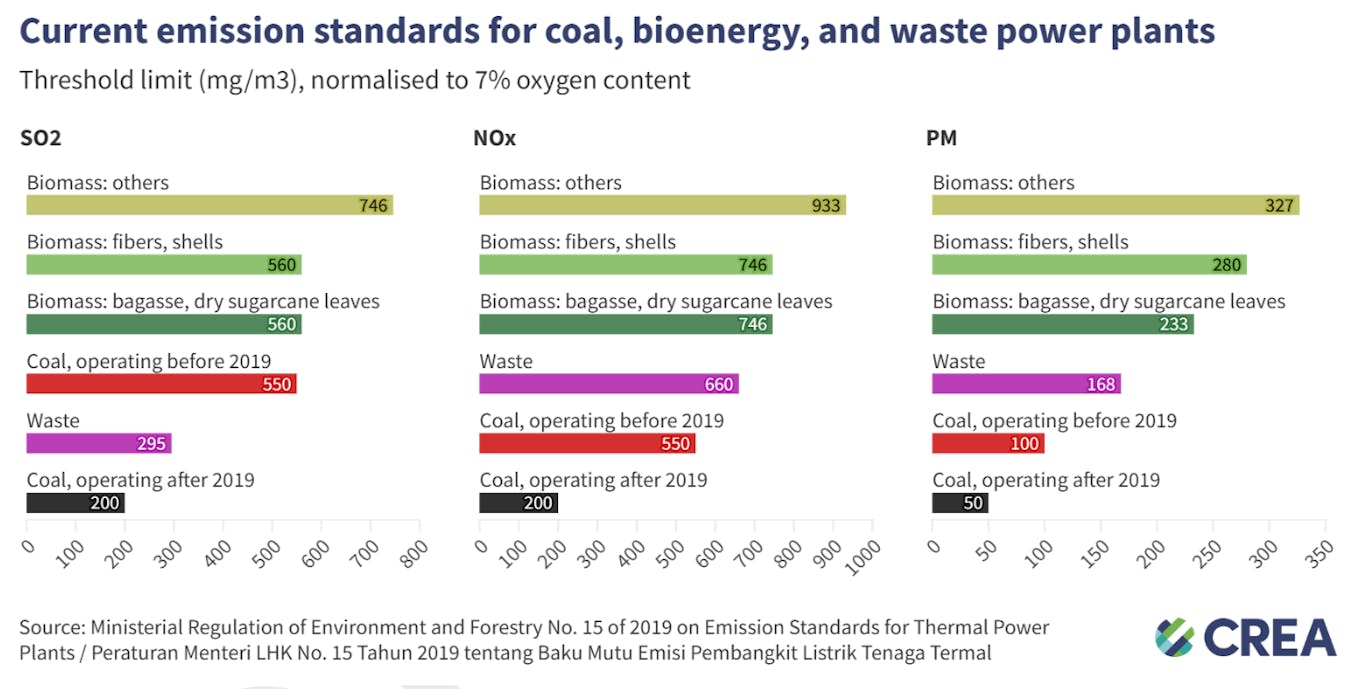

Furthermore, emission threshold limits set for coal and biomass power generation differ, where biomass power plants are allowed to release higher levels of PM, NOx and SO2. The limit for mercury release in biomass power plants is also about 150 times higher than what is currently enforced for all coal power plants.

Indonesia’s current emissions standards do not clearly outline what are the applicable threshold limits for biomass co-firing plants.

Indonesia’s emissions standards for power generation using coal before and after 2019, biomass and waste. The threshold limits for coal plants with biomass co-firing remain unclear. Image: CREA

In addition, claims on emissions mitigation from biomass co-firing in PLN’s coal plants have not accounted for the life cycle emissions of the biomass supply chain, including the harvesting, processing and transportation of the feedstock.

As of 2024, PLN has implemented co-firing in 47 of its coal plants, with plans to expand it to all 52 units this year. It also aims to distribute 3 million tonnes of biomass for co-firing in 2025, up from 1.65 million tonnes last year.

The majority of Indonesia’s biomass co-firing plants are located in Java, where the boilers can only take smaller size inputs, such as sawdust and woodchips. Meanwhile, coal plants in other islands use other boiler types that are equipped to handle larger-sized feedstock like palm kernel shells, corn cobs, agricultural waste and other woody materials.

But securing sufficient biomass supply has been challenging, even in the early stages of co-firing at a low ratio, given PLN’s low reference price for biomass – which unlike coal, varies according to the feedstock type, distance transported and export market demand.

“PLN’s role as the sole off-taker for biomass creates a monopolistic market environment that leaves producers vulnerable to unfavourable pricing schemes,” said CREA.

“This is further compounded by a growing export market to Japan and South Korea. Instead of addressing these fundamental issues or shifting focus to other promising renewable sources such as solar, wind, geothermal, and hydropower, national stakeholders remain committed to biomass co-firing, merely pushing the 2025 target of 10.2 million tonnes of biomass use to 2031.”

The highest price that biomass feedstock fetches domestically is US$51 per tonne, while exports are priced at much higher ranges. For instance, exports of wood pellets and wood chips are in the range of US$90 to US$130 per tonne, palm kernel shells are priced at US$100 to US$135 per tonne and corn cobs at US$135 per tonne.

The growth in profitability of Indonesia’s export-oriented biomass market has been driven by Japan and South Korea – the second and third largest global wood feedstock importers. Between 2021 and 2023, the two markets have captured nearly all of Indonesia’s wood chips and wood pellets exports, with the latter growing by 1,000 fold.

Last year, climate advocacy group Solutions for Our Future (SFOC) estimated that burning wood to reduce coal use by 10 per cent in PLN’s power plants could trigger the deforestation of an area roughly 35 times the size of Jakarta and result in carbon emissions almost 500 times higher than current levels.

While over 1.2 million hectares of so-called “energy plantation forests”, or areas to plant fast-growing trees to be cut and chipped for feedstock, have been set aside by the government, SFOC said that their estimates show that more than 400,000 hectares of undisturbed tropical forest within these plantation forests could be threatened with increasing pressure to meet projected demand and foreign demand for woody biomass.

“Meeting the country’s co-firing mandate could require 10.23 million tonnes of wood pellets a year… potentially driving deforestation rates as high as 2.1 million hectares a year,” stated the non-profit.

“Existing biomass feedstock sources are insufficient to meet the future demand for co-firing in coal-fired power plants, thereby driving the expansion of [energy plantation forests] as an inevitable measure to secure continuous biomass supply,” said Fiorentina Refani, director of socio-bioeconomy studies at Centre of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), a Jakarta-based research institute. “This serves to demonstrate how the sustainability narrative that has been attached to biomass co-firing is a mere myth.’

Mounting criticism about the unaccounted climate impacts of biomass energy in the past year led South Korea to announce a major reform last December to end subsidies for new biomass projects and state-owned co-firing facilities from 2025 onwards. It also committed to reducing support for existing plants using imported forest biomass, which advocates – including SFOC – hailed as a significant step towards alleviating pressure on forests threatened by Asia’ growing biomass market.

Calls for a ‘fact-based roadmap’ for bioenergy

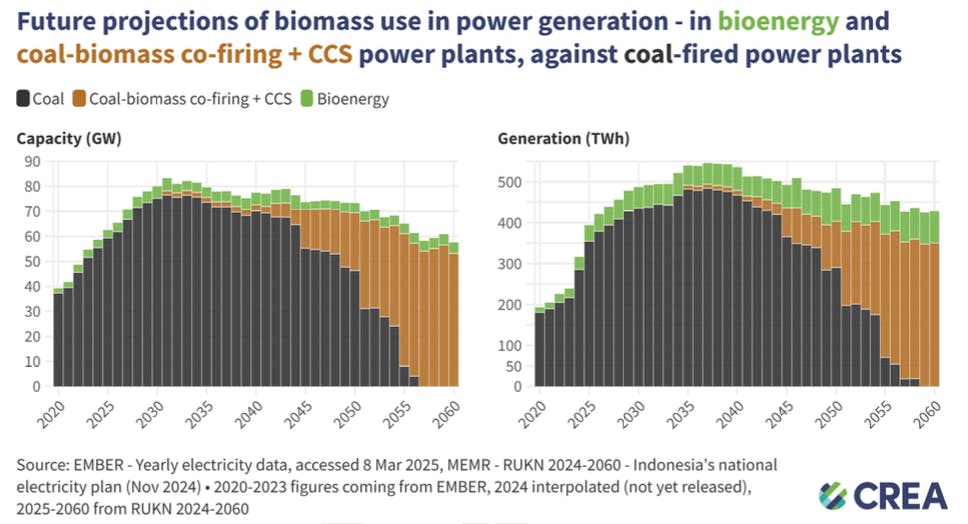

While Indonesia’s latest national power plan released this week has significantly reduced bioenergy targets, it doubled down on plans to abate coal power through the use of carbon capture and storage (CCS) and co-firing biomass.

According to Indonesia’s last Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), power generation shares of renewables and bioenergy with CCS or co-firing plants connected to CCS are expected to reach 43 per cent and 8 per cent respectively by 2050.

Projection of biomass use in Indonesia’s power generation, including both grid-connected and captive coal power plants. Image: CREA

In response to the public consultation of its second NDC, which was due for submission in February but has yet to be submitted, civil society groups expressed major concerns over the high reliance on bioenergy plans in decarbonising the power sector, highlighting deforestation risks and conflicts with its target for the forestry and other land use (FOLU) sector to be a net carbon sink by 2030.

In order to justify bioenergy as a green initiative, CREA called for PLN to require independent verification of emissions released throughout the value chain and to create a framework that enables proper plant-level assessment for all bioenergy use, including co-firing in coal plants.

“The main issue with biomass co-firing is that national stakeholders view it as a viable solution to mitigate Indonesia’s fossil fuel emissions rather than truly addressing the root causes of air pollution or prioritising accelerated deployment of renewable energy sources,” said Abdul Baits Swastika, a researcher at CREA. “Not backed by transparent and thorough assessment, these claims need to be questioned and a fact-based roadmap for bioenergy should be provided.”

Inaccurate claims that have been made about bioenergy’s potential to mitigate emissions and health-harming pollutants should, however, serve as an “entry point for a more rounded national discussion on air quality,” said Katherine Hasan, an analyst at CREA. “[Air quality] can only be improved when we recognise the urgency to map a retirement pathway assigned to all coal power plants in Indonesia – on-grid and captive.”

Stringent emissions standards, including the installation of air pollution control technologies in all power plants, are key to truly mitigating emissions in coal plants, Hasan added.

Putra Adhiguna, managing director at Australia-headquartered non-profit think tank Energy Shift Institute, said that while biomass co-firing has been offered as a solution for several years, there remains little clarity on how biomass will be sourced sustainably and be reliably scaled up.

“Scrutiny on biomass use is rising in many countries, especially if such risks are not managed. South Korea reportedly ending subsidies for biomass is a telling sign of waning support globally,” he said.